Chest deformities are a relatively rare problem for teenagers but can greatly affect their self-esteem and might lead to difficulties in the functioning of their heart and lungs. Fortunately, minimally invasive techniques are available at our hospitals that can safely return chests to a normal shape.

Knocking body confidence

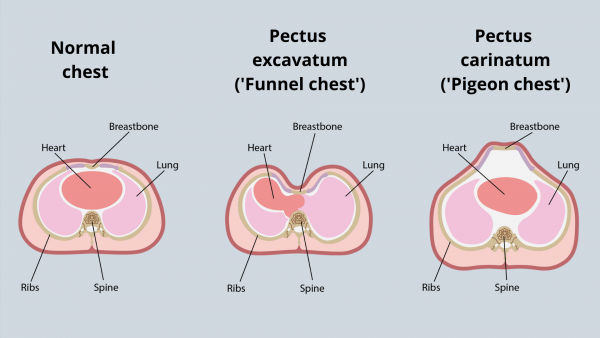

The two most common chest deformities are called pectus excavatum (‘funnel chest’) and pectus carinatum (‘pigeon chest’). They occur when the breastbone – which runs down the centre of the chest – sinks in (funnel chest) or protrudes out (pigeon chest) of the chest.

It is not known exactly how these conditions occur, but it is thought to be due to the cartilage (the smooth, flexible tissue in between bones) of the ribcage overgrowing. These conditions may not be obvious in childhood and present themselves mostly during the growth spurts of adolescence.

They occur more often in boys than girls and are relatively rare disorders affecting about 1 in every 1,000 children for funnel chest and 1 in every 1,500 for pigeon chest. As these conditions appear to run in families, there may be a genetic link.

As the ribcage is more rigid than normal for both conditions, they can result in difficulty breathing, chest pain and an irregular heartbeat – particularly on physical exertion. However, the main impact is psychological.

Due to the chest’s appearance, the conditions can cause significant embarrassment for children, resulting in low self-esteem and clinical depression. They often exclude themselves from social and sporting activities, particularly those that require them to expose their chests such as swimming.

Correcting deformities with minimally invasive techniques

Past procedures to correct chest deformities were very invasive and involved surgically removing the deformed cartilage around the breastbone and fixing it into a normal position using metal and mesh supports. Fortunately, less invasive techniques are now available.

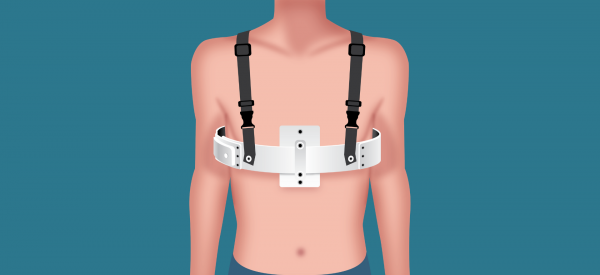

Pigeon chest can be treated with a chest brace which applies pressure to the front and back of the ribs to gradually move the breastbone back to where it should be. The patient wears the brace for anything between a couple of months up to few years depending on a few variables and the severity of the deformity; ideally the brace should be worn as many hours a day as possible, but it could be removed for showering or sporting activities.

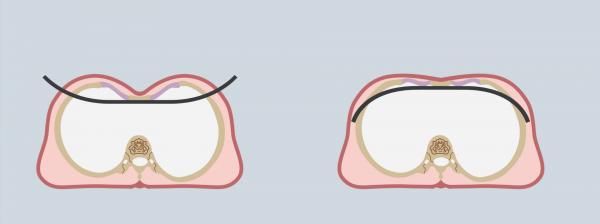

Funnel chest can be treated with the minimally invasive Nuss surgical procedure. Small incisions are made either side of the chest and one to three curved metal bars are placed behind the breastbone to push it into a normal position. The bars are kept in place for one to three years before removing – after which time the ribs stay in their new shape.

The Nuss procedure for pectus excavatum (funnel chest). Metal bars are inserted through incisions on either side of the best and flipped up to lift the breastbone to a normal position.

It is not known exactly how these conditions occur, but it is thought to be due to the cartilage (the smooth, flexible tissue in between bones) of the ribcage overgrowing. These conditions may not be obvious in childhood and present themselves mostly during the growth spurts of adolescence.

They occur more often in boys than girls and are relatively rare disorders affecting about 1 in every 1,000 children for funnel chest and 1 in every 1,500 for pigeon chest. As these conditions appear to run in families, there may be a genetic link.

As the ribcage is more rigid than normal for both conditions, they can result in difficulty breathing, chest pain and an irregular heartbeat – particularly on physical exertion. However, the main impact is psychological.

Due to the chest’s appearance, the conditions can cause significant embarrassment for children, resulting in low self-esteem and clinical depression. They often exclude themselves from social and sporting activities, particularly those that require them to expose their chests such as swimming.

Correcting deformities with minimally invasive techniques

Past procedures to correct chest deformities were very invasive and involved surgically removing the deformed cartilage around the breastbone and fixing it into a normal position using metal and mesh supports. Fortunately, less invasive techniques are now available.

Pigeon chest can be treated with a chest brace which applies pressure to the front and back of the ribs to gradually move the breastbone back to where it should be. The patient wears the brace for anything between a couple of months up to few years depending on a few variables and the severity of the deformity; ideally the brace should be worn as many hours a day as possible, but it could be removed for showering or sporting activities.

Funnel chest can be treated with the minimally invasive Nuss surgical procedure. Small incisions are made either side of the chest and one to three curved metal bars are placed behind the breastbone to push it into a normal position. The bars are kept in place for one to three years before removing – after which time the ribs stay in their new shape.